I was inspired by a podcast called The 500 hosted by Los Angeles-based comedian Josh Adam Meyers. His goal, and mine, is to explore Rolling Stone Magazine's 2012 edition of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Album: #198

Album Title: The Best of Little Walter

Artist: Little Walter

Genre: Blues

Recorded: May, 1952 - January, 1955

Released: 1958

My age at release: Not born

How familiar was I with it before this week: Not at all

Is it on the 2020 list? No

Song I am putting on my Spotify Playlist: Juke

Although I’ve improved, I am prone to shooting myself in the foot. Sometimes, I recognize I am doing it in real time. I’ll feel myself making an ill-advised decision and ignore every impulse to change course. It’s as if both my ego and superego are standing at a fork in the road frantically waving their arms and screaming for me to veer left. All the while, my Freudian Id is white-knuckling the steering wheel, banking hard to the right onto the precipice of social calamity.I’m not alone. Psychologists recognize that, particularly when under stress, humans tend to retreat to habits of emotional regulation that were formed when they were young. Our Id takes over and our emotions and behavioural choices figuratively become driven by a toddler. We act impulsively, eschew judgment or foresight and declare, “No! My Way!"University of Maryland professor Dr. Steven Stossy says:“The Toddler brain is dominated by feelings rather than analysis of facts. (If the feelings are negative, they seem like alarms.) Not surprisingly, habits formed in the Toddler brain are activated by feelings rather than analysis of the conditional context of past mistakes and their consequences. When we feel that way again, for any reason, past behavioral impulses grow stronger, increasing the likelihood of repeating the mistake.”Such was the fate of American Blues musician Little Walter whose short life was punctuated by alcoholism and avoidable violence due to his legendary temper.Marion Walter Jacobs was born in Marksville, Louisiana, sometime between 1923 and 1930. There are no birth records and Jacobs often changed his date of birth when completing government documents. This was likely so that he could sign performance contracts when he wasn’t at the age of majority. He quit school early, likely at 12, so he could travel to several cities, including New Orleans, Memphis and St. Louis. There, he worked odd jobs and busked on the streets with his harmonica and guitar. During that time, he came under the tutelage of legendary blues performers such as Sonny Boy Williamson and Honeyboy Edwards. Diminutive in stature, but large in personality, he began using the pseudonym Little Walter. Some of his contemporaries sometimes added a four letter expletive in the middle of his name because of his fiery temper. Behind his back, he became “The Little (****) Walter”.Like many musicians from the southern states, Jacobs eventually made his way to “The Windy City” of Chicago. Nestled on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan, the major metropolis had become the hub for the blues. There are a few factors that contributed to this:

- A mass migration of African Americans began with the end of the Civil War and continued through the early 1900s. The population shift was due to the implementation of “Jim Crow Laws” in the southern states, which codified racial segregation and made upward wealth mobility nearly impossible for black citizens.

- The newly completed trans-continental railway system allowed for reasonably priced passage to the north …and Chicago was the end of the line.

- The tradition of African American folk music and acoustic southern blues, or country blues, travelled north with the migrants. Chicago had been powered by electricity since 1888 and recording studios and nightclubs were abundant.

- Additionally, the electric guitar was introduced in the late 1930s and blues musicians in Chicago adopted amplification. The sound changed, eventually leading to Rock and Roll.

|

| Little Walter statue in Germany. |

|

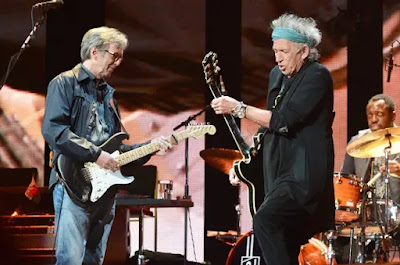

| Keith Richards and Eric Clapton performing in 2013 |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment